Guest post: This is why we do what we do

Our Development Director, Cheryl, approached James Buzard, a well-traveled writer and major fan of world music, to write a guest post that might be able to put into words why we do what we do here at World Music/CRASHarts. Its the power of the music and the respect for the artists. Its the community we build during our concerts and performances. Based on his credentials alone, I think he can describe the passion for world music better and more articularly than I can!

Read, enjoy, share, comment.

Who can explain how it happens? “I heard it and liked it”: so superficial. Why did I like it? But even that’s the wrong question, because the relationship I’m trying to express eludes capture by the word “like.” I didn’t just “like” it; it got inside me, it took me over. I’m talking about my encounter with the phenomenon we awkwardly call “world music.” I’m sure you know the feeling. Not all of it, of course: some of the most famous names still leave me strangely cold. But the stuff that grabs me – how to account for its power, its capacity for insinuating itself into my bloodstream and dominating my mental soundtrack? It comes winging out of Mali or Zimbabwe or lots of other places, sometimes hits the stage at the Somerville Theater (thanks to the efforts of World Music/CRASHarts) or at other locales, and makes its claim on the heart of this bourgeois white guy from upstate New York. How? How come? Nothing in my background would have suggested that I would respond to it the way I did. I had a wholly conventional American upbringing during the ‘60s and ‘70s – too young for Vietnam, the counterculture, the “British Invasion” (I have to confess to still being lukewarm on the Beatles!), and with no broader horizon that what played on the radio out of Syracuse or Binghamton. Over the decades, opportunities to travel certainly widened my horizons, but the music I’m thinking of, which I didn’t discover until my forties, comes mostly from places I’ve still never been.

I remember with startling clarity a day in 2002 when I first heard Oliver Mtukudzi (“Tuku”). It was in a Borders bookstore (remember those?), in the music section, where an album called Vhunze Moto sat on a Putumayo rack in a corner. Passing time, I put on the headphones and “Ndakuvara” came on. Eureka. Life would never be the same. What was it? The gravelly voice, surely, and the forceful rhythm and the way the backup vocals mixed in, and the gorgeous restraint of the overall sound – but can this itemizing of details ever grasp the captivating gestalt? Did I buy the album that very day? It wasn’t long before I did, and then Tuku Music and Paivepo and Neria and Ziwere MuKobenhavn and Bvuma … and so on. Pretty soon I was tracking down the harder-to-find albums. I even managed to download a live concert and press it onto a CD. It opens with the haunting “Mupfumi Ndiani,” a song that had been recorded on an earlier album with terrible sound quality but was now restored to inspiring life, with a sharper rhythm and more focused emotion. (Many of the early albums suffer from murky sound; thank goodness for the remastered collections that provide generous samples of Tuku’s work from 1984-1991 and 1991-1997.) The concert version of “Mupfumi Ndiani” starts slow and spare, propelled forward by the yank of the upbeats. As it proceeds, Tuku grows increasingly impassioned, crying out for release or redemption, and a backup singer’s delicate tenor floats above his lines like a coasting dove from heaven, like the grace he’s praying for. The song draws to a close with a return to peace and simplicity, the burdens of the middle part perhaps not lifted but shouldered once more with renewed resolution. Paivepo’s “Ndine Mubvunzo” works in a similar way: it’s a desperate appeal that gathers to cathartic intensity and then winds down toward calm through an incantatory repetition of vowels – ha, heh – as the tempo slows to a stop.

I remember significant moments in my life through their association with world music songs I was listening to or remembered at the time. There’s a certain Habib Koité tune, “Saramaya,” from the album Ma Ya, the delicious rhythmic drive of which is forever connected, in my mind, with another sort of drive, the exhilarating car trip I took one fine August day up Highway 1 from Santa Cruz to San Francisco with a woman with whom I was then very much in love. The music coursed through me, down my leg and through the foot that pressed the accelerator as we ascended those successive rolling rises along the Pacific coastline in the benevolent sunshine. (I do this sort memory location with selected Western music, too, but a lot of popular music in the West strikes me as overproduced, slick, banal, formulaic. In the world music that I love I hear something different, and I don’t know whether that’s simply because it comes from those places distant and alien to me – which would be strange, because I feel so much more at home with it than I do with most American pop.) Habib was my second discovery, probably thanks to Putumayo as well, and I’ve been following him as assiduously as I do Oliver Mtukudzi. I’ve seen the latter maybe a dozen or more times in concert, in various places, the former maybe eight to ten times. I’ve been known on more than one occasion to fly to a city because one of these performers will be appearing in it.

Maybe it’s futile to attempt a description of one’s relationship to music; maybe the experience is just too ineffable to be described. Maybe one can only go on pointing to individual instances – like the time I first heard Mtukudzi live, on a splendid afternoon in a San Francisco park and he played “Neria” – on the album, six minutes and six seconds of simple perfection – and I wanted to just lie on the ground and weep for joy. Bonnie Raitt came out to sing “Help Me Lord” with him that day. Or there’s the way a certain pause in “Magumo” always sends a chill down my spine. Or the way “Kunze Kwadoka” and “Mutsererendende” compel me to start swaying, whatever else I’m doing. Or how it feels when I’m on the elliptical machine with “Wake Up” in my ears, pushing me onward (it too ends with an incantation and moves from crisis toward recovered calm). Or how it feels to surrender to the beautifully controlled call-and-response of “Ndagarwa Nhaka.” Or how, one time, Tuku opened his concert with “Andinzwi,” a song I had never really loved on his solo album Ndega Zvangu, but which this time, with backup vocals hovering above him, took on a whole new dimension. I remember how gracefully the ensemble moved, and how, when they wanted to fade out, they simply backed away from the microphones step by step. It was magical. Oh, one could go on and on. The danger is like that that attends on the narration of one’s dreams: you can never quite capture in words what captivated you so much in the moment.

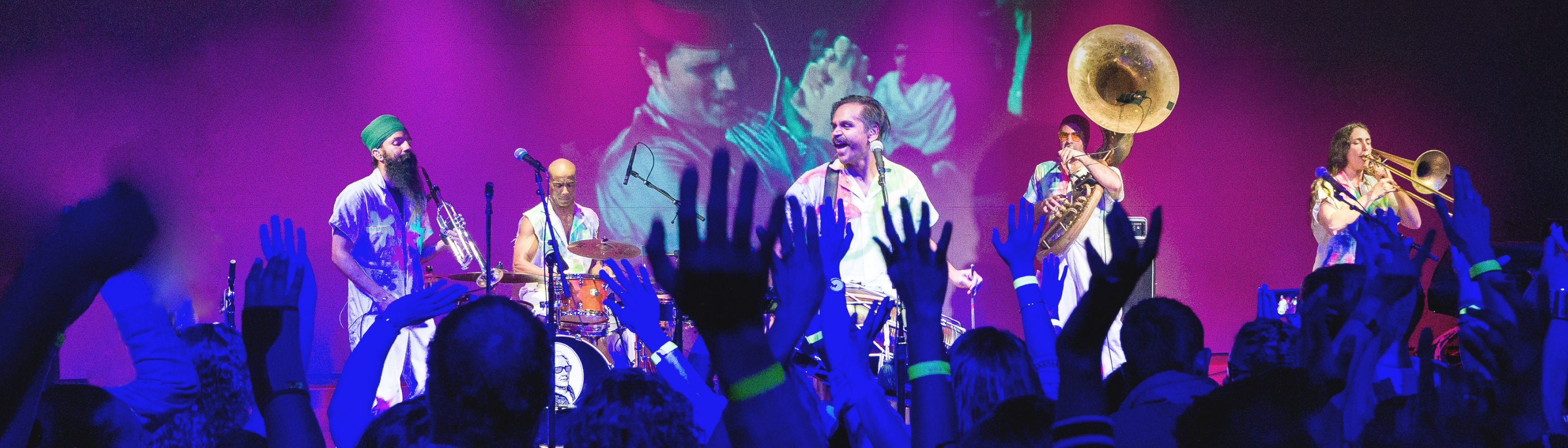

I’ve often wondered if not understanding the words liberates me to focus on the rhythms, the sounds, the interplay of voices. I must admit that a kind of rule has begun to force itself upon me: for the most part, with some exceptions, if the world music artist sings in English, the song is likely to be unsuccessful. The emotions will seem banal, the command of English inadequate, the sentiments feeling tailor-made to suit the crossover audience the artist might imagine to be there. Of course, I recognize the possibility that, if the lyrics in the original languages were rendered into English, they too might seem banal. This is popular music, of course, so one doesn’t expect Shakespearean sonnets. One of Habib Koite’s recent songs, “L.A.,” for instance – a super-light but catchy tune about the joys of drinking tequila – fits into this category, but one can excuse it: it takes the place once occupied in his concerts by the equally frothy but irresistible “Cigarettes A Bana,” about running out of smokes during a recording session (a song that, ironically, got turned into an anti-smoking anthem in Mali.) More debilitating are the songs that wind up sounding both pious and ungrammatical, such as the otherwise lovely “Kumbin” from Habib’s album Ma Ya. A song like this makes you feel it was written for a Western audience Habib had not yet really come to understand: it’s at once beautiful and trite, and a little embarrassing. But he’s so great an artist that I don’t even skip over it any more when I’ve got the album on. Tuku has songs like this, too, such as “Rurimi,” on Bvuma. This is a song with gorgeous sections, the English parts of which are really awkward. But with all great artists, it isn’t the avoidance of mistakes that makes them great. They take risks, some of which don’t pay off. What matters is the richness of the very considerable remainder. Go listen to Ma Ya or Baro by Habib Koite; try Paivepo and Tuku Music by Oliver Mtukudzi. Don’t put it on as background music. Cook to it, or relax to it, or dance to it. Have it in your earphones the first time you hear it. I hope you’ll see what it does for me, and I look forward to seeing you at a future concert. –-James Buzard, May 2014

Listen to some of the artists James finds particularly inspiring on this Spotify playlist (along with some of my own personal recommendations). *Will launch Spotify player.

James Buzard works on 19th- and early 20th-century British literature and culture, with particular interest in the Victorian novel (Dickens, George Eliot, the Brontës, and others), modernism, the history of travel, and theories of culture and society. In addition to teaching on these topics, he enjoys teaching “great books” surveys such as Foundations of Western Culture: Homer to Dante and Forms of Western Narrative. He is the author of The Beaten Track: European Tourism, Literature, and the Ways to “Culture,” 1800-1918 (Oxford 1993) and Disorienting Fiction: The Autoethnographic Work of Nineteenth-Century British Novels (Princeton 2005), as well as of numerous articles in journals and books. He is also a contributing editor of Victorian Prism: Refractions of the Crystal Palace (Virginia 2007), a collection of essays on the impact of the Great Exhibition of 1851. He has been known to tread the boards in Gilbert & Sullivan. He is both drawn to and wary about the revolving door.